picking up needle and thread

deborah valoma

When I was nineteen, my grandmother Sara Sohigian Magarian, a skilled needleworker, taught me the basic Armenian needlelace stitch. We were standing in her Fresno kitchen, when my grandfather, a mechanical engineer and graduate of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, commented nonchalantly: “I could build a machine to make that faster and better.” Not just faster, but better.

He was wrong of course; only a poor imitation of the knotted technique could be mass produced. But the moment was pivotal. His remark became a call to action that propelled me along an esoteric career path. Threadwork became my academic focus and creative medium: I perfected many textile skills such as weaving, spinning, and crocheting, but only turned to my grandmother’s needlelace tradition in recent years after inheriting my grandmother’s textiles collection.

As I wrote in the essay “Thread Memory” in the anthology 23:5 to be published in 2026 by the Hrant Dink Foundation in Istanbul.

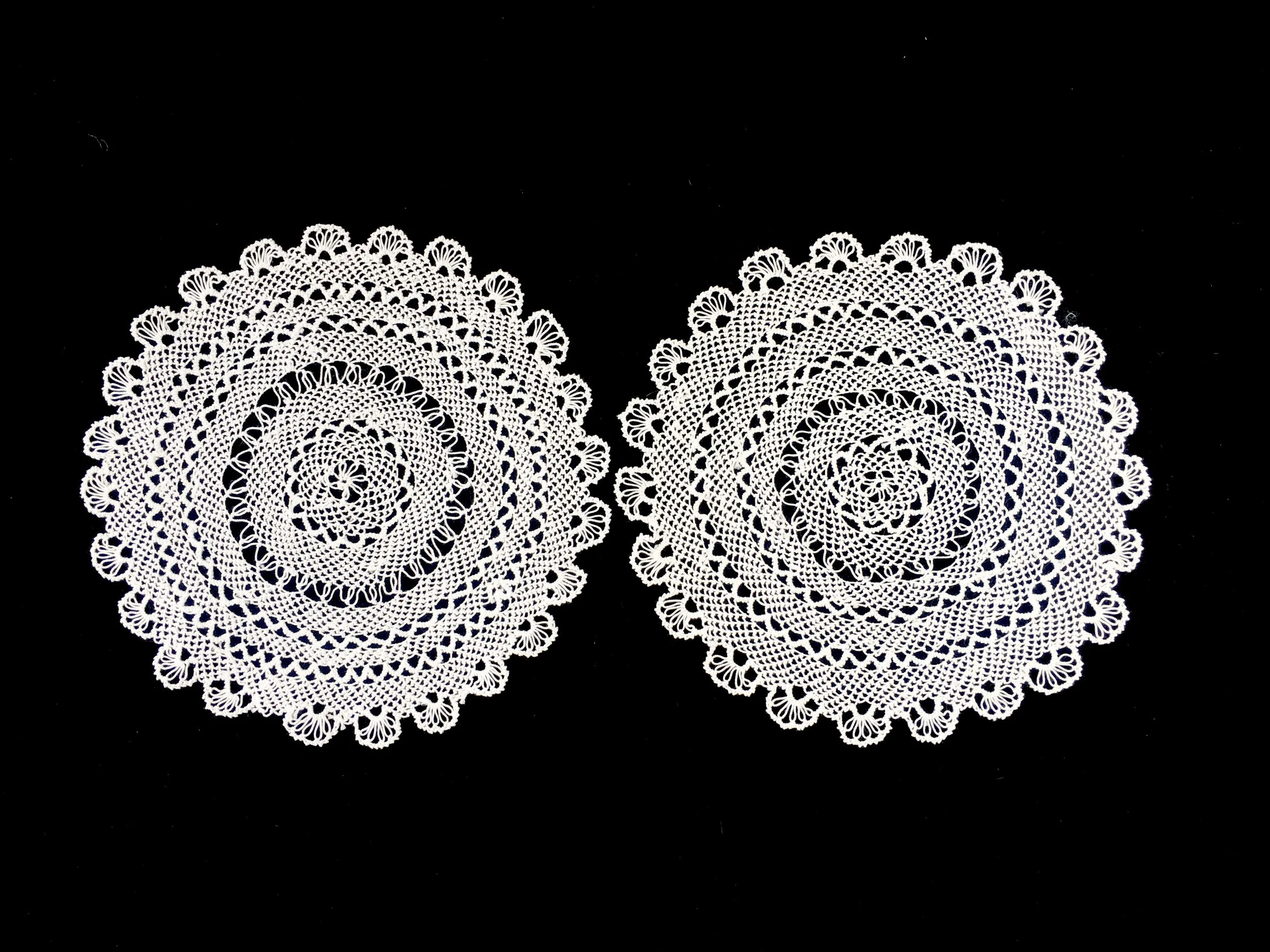

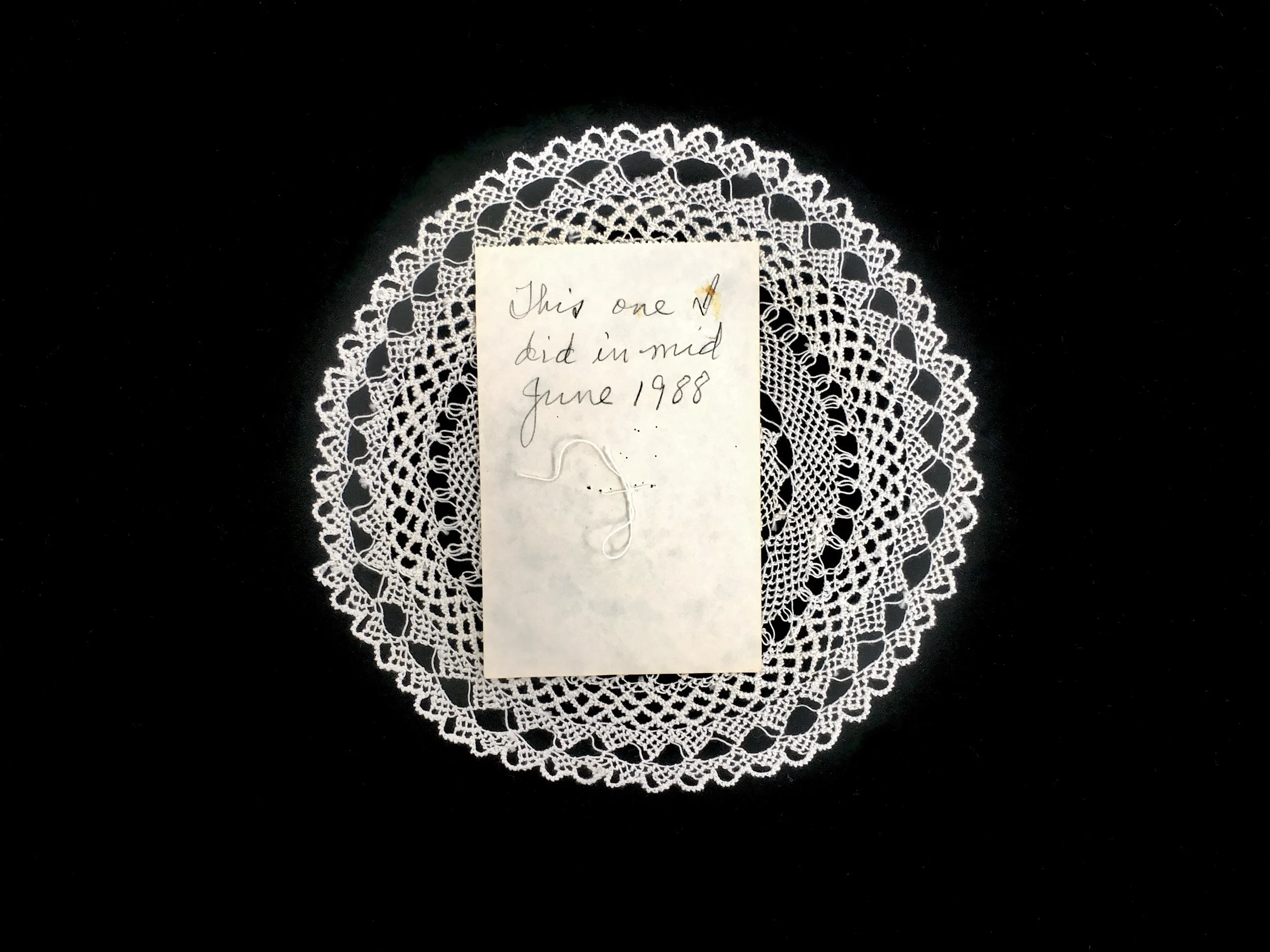

My grandmother stitched needlelace every evening throughout her life, working wordlessly with head bowed. Her posture was seemingly benign, but this “silent memory work” [1] should not be dismissed as inconsequential. Ubiquitous in the everyday, textiles are disguised as merely decorative; but behind the gendered notion that female-identified work is barren of content, stitching can be a formidable act. [2] As my grandmother aged, her stitches became unsteady and doilies miniature – a trajectory reflecting an art form in jeopardy. But as evidenced by the hundred needlelace medallions I inherited, she did not waver in her mission to materialize memories of a homeland she had never set foot on.

Picking up needle and thread became a professional calling and personal act of defiance. I embraced needlelace—one of the slowest and most technically challenging of all women’s work—in order to reclaim respect for an art form deemed feminine, frivolous, and antiquated—a so-called waste of time in a male-dominated world oriented to 24/7 production schemes.

But it became something more complex. Like other indigenous textile genres that I have taught and written about, I realized that my own was also in jeopardy. And like other cultural movements that revive old ways to salvage ancestral knowledge, carrying the thread forward is a declaration of identity and a strategy of cultural stewardship. Actively making, researching, and writing breathes life into a legacy practice gasping for air.

[1] Carol A Kidron. “Toward an Ethnography of Silence: The Lived Presence of the Past in the Everyday Life of Holocaust Trauma Survivors and Their Descendants in Israel.” Current Anthropology 50, no. 1 (2009): 6.

[2] Catherine Dormor. “The Event of a Stitch: The Seamstress, the Traveler, and the Storyteller.” Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture 16, no. 3 (2018): 305.

Sara Sohigian before her marriage to Masik Magarian, San Francisco, ca. 1928. © Deborah Valoma.

Sara Sohigian Magarian, twin needlelace doilies, ca. 1960–70. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2018.

Sara Sohigian Magarian, needlelace doily, 1988. Note stitched to doily reads: "This one I did in mid June 1988." Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2018.