into my open waiting hands

deborah valoma

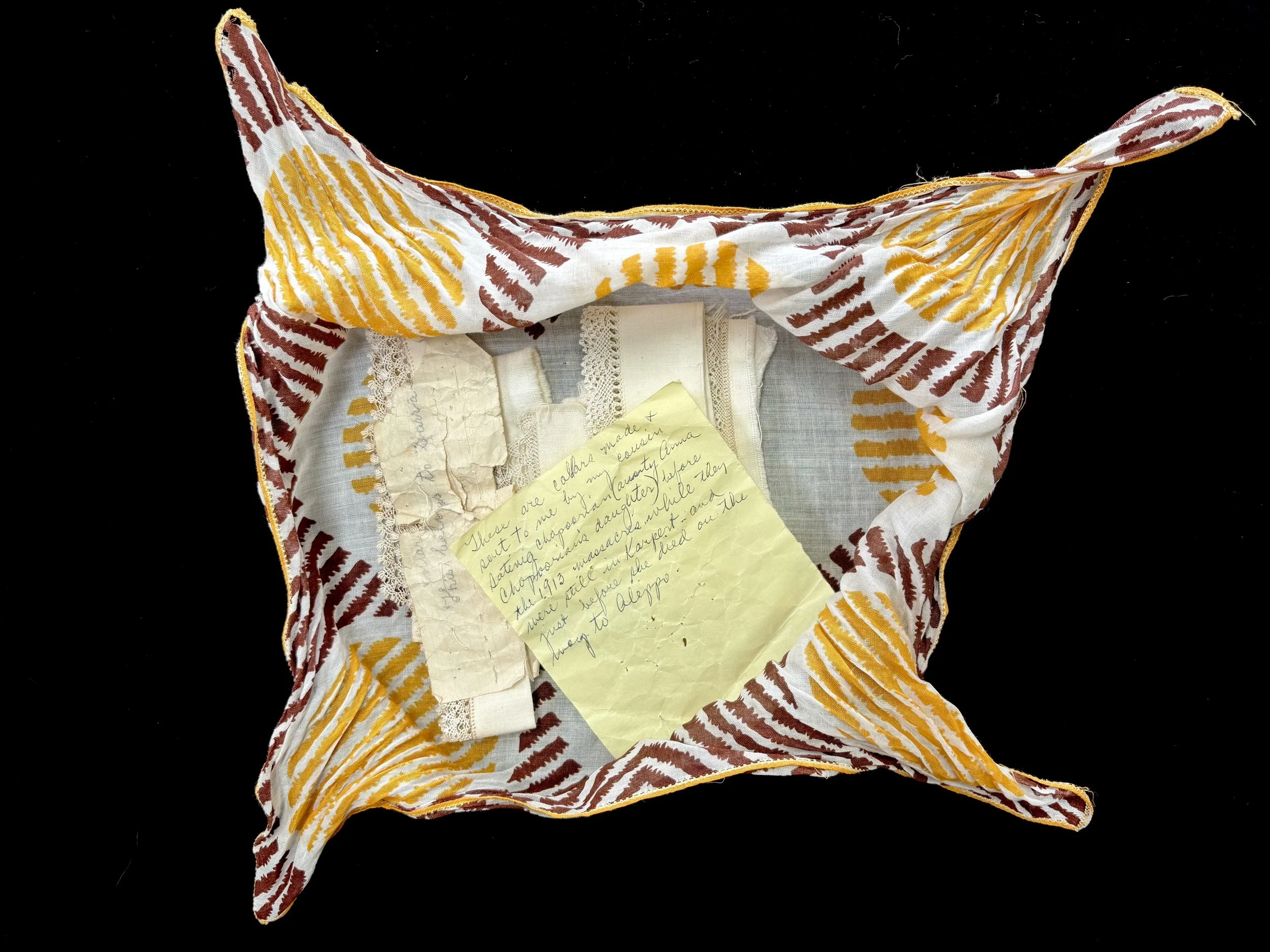

When I first opened the cedar chest and boxes packed with my grandmother Sara Sohigian Magarian’s textiles years ago, I found three cotton collars trimmed with Armenian needlelace tucked into a knotted handkerchief. A note in my grandmother’s handwriting said: “These are collars sent to me by my cousin Satinig (auntie Anna Chopoorian’s daughter) before the 1913 [sic] massacres while they were still in Kharpert—and just before she died on the way to Aleppo.”

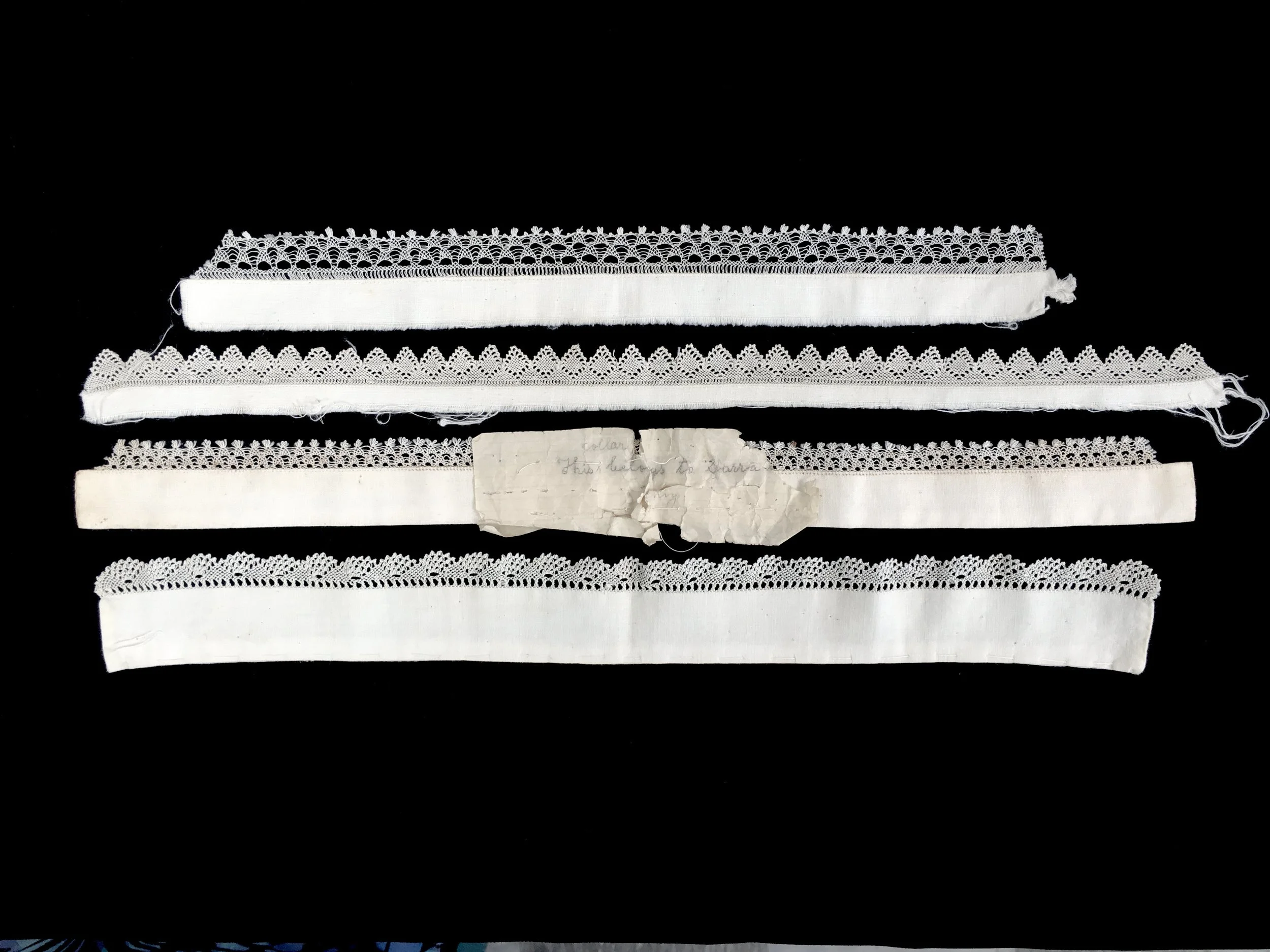

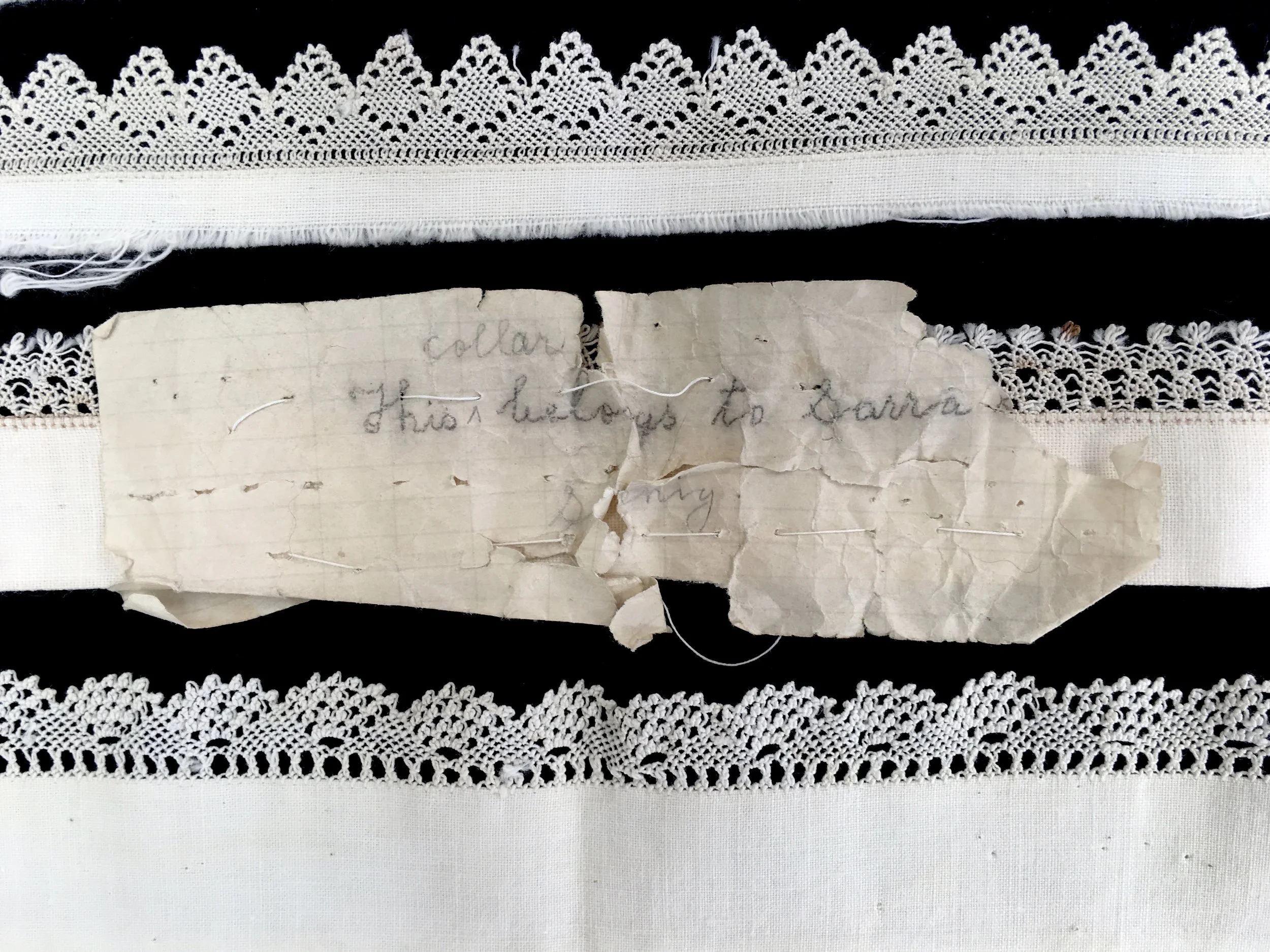

The collars were trimmed with ultrafine needlelace, each with a meticulous, and yet, distinct pattern. Presumably made by my grandmother’s cousin, I have envisioned Satinig taking the collars off her blouses and, in a prescient moment, sending them to her first-cousin Sara in Fresno-–then only a child of perhaps four. Many years later, I discovered a fourth. Stitched to it was a scrap of faded school paper bearing an English inscription scribed in pencil: “This belongs to Sarra [sic].”

Born in 1892 in Hussenig, “a majority Armenian town in the shadows of the Kharpert fortress,” [1] Satinig was the daughter of Kirkor Chopoorian and Anna Sohigian Chopoorian. Anna was the sister of my great-grandfather Hamparsoum Sohigian, who had emigrated to the United States in 1888 to meet their elder brother Hovhaness in Chicago.

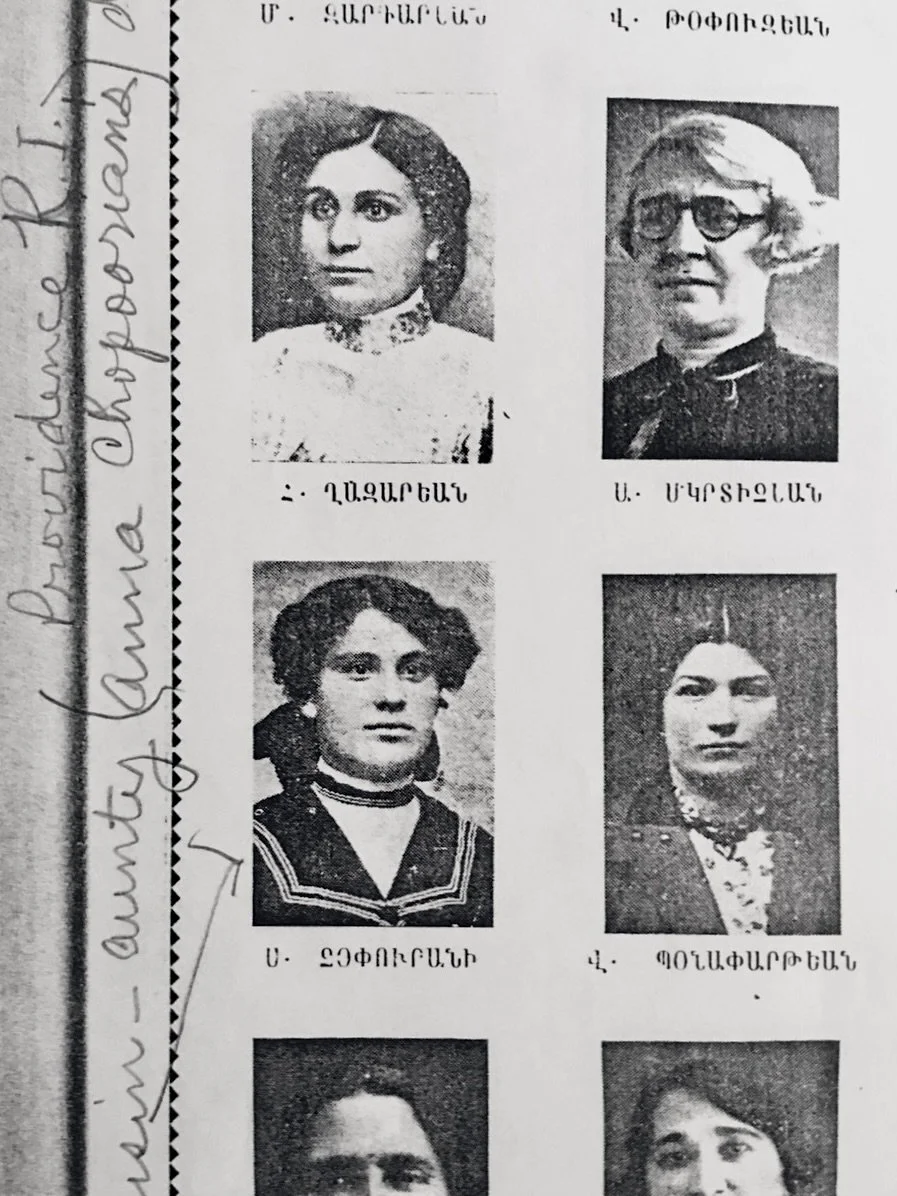

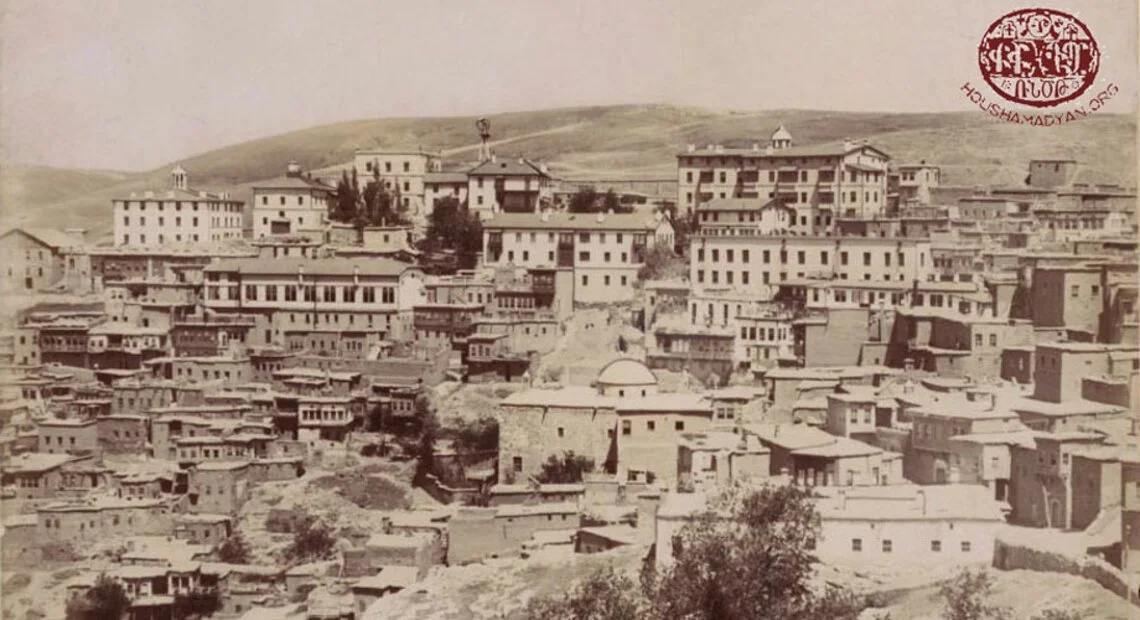

Satinig had been a high school student at Kharpert’s Euphrates College (1852-1915), a well-known missionary institution that included a theological seminary, hospital, orphanage, and high school for both boys and girls. A 1942 publication about the school shows an image of Satinig—one of the few that exist—and cites her graduation date as 1913. [2] But when deportation orders were announced in Kharpert on July 1, 1915, buildings at the college were commandeered and occupied by the Ottoman army, and leading Armenian members of the faculty were arrested, tortured, and executed. [3]

Anna’s husband Sarkis had already emigrated to the United States by 1915, possibly to pave the way for his wife and children. The 1910 United States census shows him living in San Francisco. The family’s youngest son Marderos emigrated to the United States in 1913 to join his father, and the elder son Manign was, according to my grandmother’s notes, conscripted into the Turkish army and perished in 1916.

But little is known about the experiences of Auntie Anna and her only daughter Satinig during those perilous times. We do know that Anna, her daughter Satinig, and perhaps her sister Sultana were forced to leave their homes and walk southward toward the Syrian desert in a mass deportation march. Satinig and Sultana did not survive the brutal conditions; whether they died of starvation, dehydration, illness, or physical violence is unknown. Perhaps they threw themselves into the Euphrates River to escape torment, as women were reported to have done in a “last expression of agency.” [4]

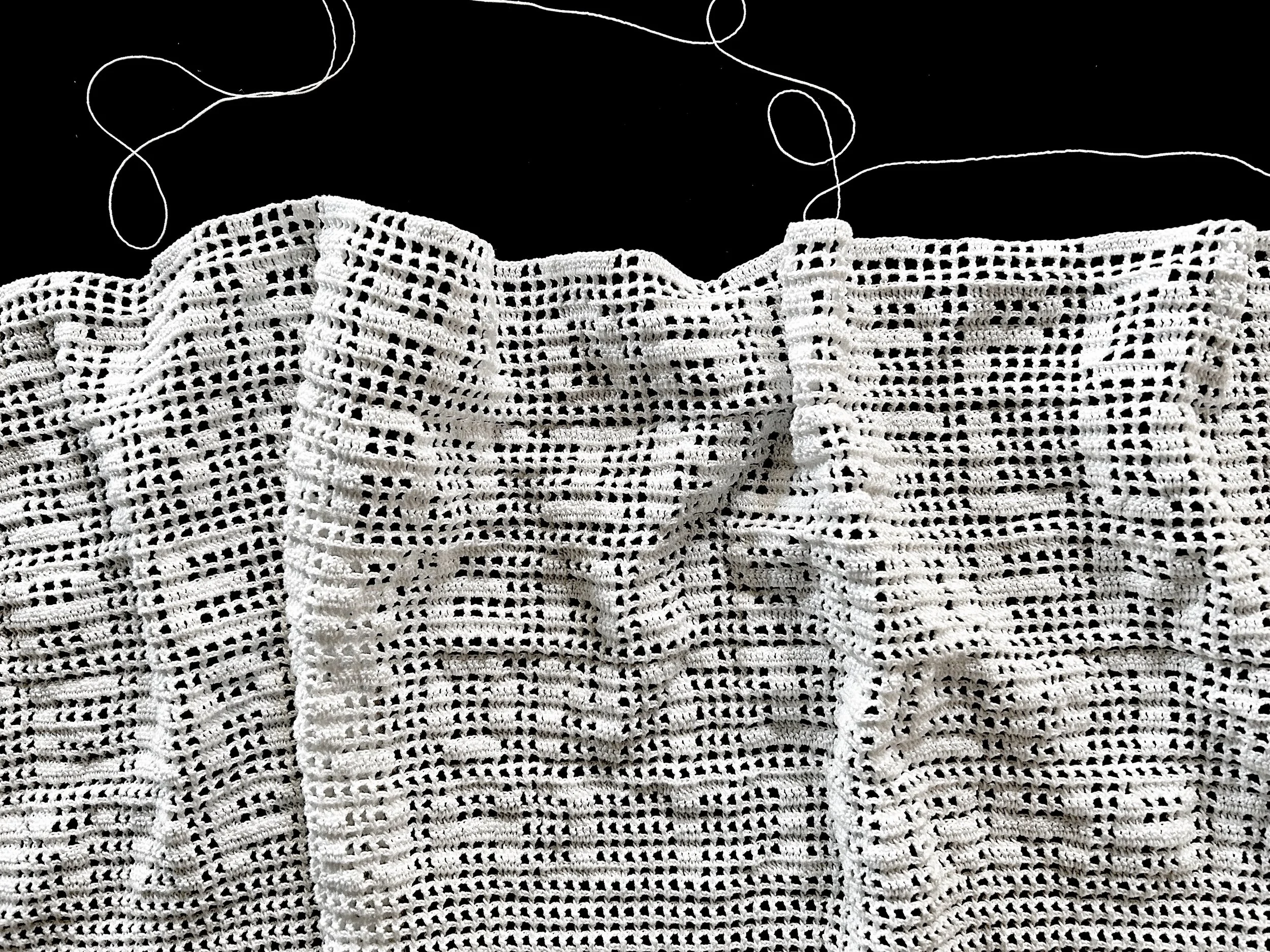

Anna survived and immigrated to the United States alone, arriving in New York City in 1920 to reunite with her husband and settle in Providence, Rhode Island. Ninety-nine years later, I visited Anna’s gravesite at the North Burial Ground in Providence. I sat quietly, leaning against her headstone, and worked the first lines of the filet crochet stitch tablecloth that, when complete, will narrate Satinig’s story. The abundant stories in our lineage of mother-daughter fissures washed over me. So many mothers and daughters were torn from each other’s arms.

Though diminutive in physical size, these four collars are the most precious pieces in my family’s textile archive. To gingerly touch the paper, fabric, and thread that Satinig touched before her tragic death is a “corporeal encounter,” defined by sensorial anthropologists as a moment of touch in which one can feel the “traces of the hand of the object’s creator and former owners.” They go on to say that “one seems to feel what others have felt and bodies seem to be linked to bodies through the medium of the materiality." [5]

Decades after Satinig’s death, her needlelace collars fell into my open waiting hands. One might wonder if this touch is, as touches are, reciprocal.

[1] George Aghjayan, “Harput Demography,” Houshamadyan, 2016. Accessed August 16, 2025.

[2] Hishadagaran Yeprad Koleji (Memoranda of Euphrates College 1878–1915), compiled by Mariam Partigian (Boston: 1942), 273.

[3] Henry H. Riggs, Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917 (Ann Arbor, MI: Gomidas Institute, 1997), 42.

[4] Elyse Semerdjian, Remnants: Embodied Archives of the Armenian Genocide (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2023), 42. [5] Constance Classen and David Howes, “The Museum as Sensescape: Western Sensibilities and Indigenous Artifacts,” in Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, eds. Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth Phillips (Berg, 2006), 202.

[5] Constance Classen and David Howes, “The Museum as Sensescape: Western Sensibilities and Indigenous Artifacts,” in Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, eds. Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth Phillips (Berg, 2006), 202.

Satinig Chopoorian, four needlelace collars, ca. early 1910s, found tucked into a handkerchief with my grandmother's note describing their origin. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2018.

Sara Sohigian Magarian Archive. Satinig Chopoorian, four needlelace-trimmed collars, Kharpert, Armenian Highlands, present-day Türkiye, early 1910s. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 1918.

Satinig Chopoorian, four needlelace-trimmed collars with paper note stitched to one, Kharpert, Armenian Highlands, present-day Türkiye, early 1910s. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2018.

Satinig Chopoorian (middle left), 1913, from the yearbook of Kharpert College where Satinig went to high school. Deborah's grandmother's notes identifying her first cousin in the margin. Photo: © Deborah Valoma.

Kharpert, ca. 1900. Upper Quarter showing the Euphrates College complex. Image accessed from www.houshamadyan.org on August 17, 2025. Source: Harvard University, Houghton Library.

Satinig Chopoorian (standing far right) with her mother Anna Chopoorian (seated with white shirt next to her brother-in-law) and Satinig's two brothers (standing in front of Sating). Satinig did not survive the death march to Aleppo. Photograph courtesy of Gregory Chopoorian, Anna Chopoorian's great-grand-nephew.

Deborah Valoma, On the Way to Aleppo. Cotton thread, crocheted in filet stitch. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2022.

Anna Chopoorian's headstone, North Burial Ground, Providence, Rhode Island, 2019. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2019.

Deborah crocheting Satinig's story at the Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2023. Photo credit: Tsovinar Kuiumchian 2023. Sadberk Hanım Museum was originally owned by the Azarian family who were Armenian Catholics from Sivas.

Deborah crocheting Satinig's story at the Imperial Harem of Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2024. Photo credit: Elise Youssoufian 2024.

Deborah crocheting Satinig's story overlooking the remains of Sourp Hagop on the eastern side of Kharpert, Türkiye; beyond are the hills where the Euphrates College once stood, 2025. Photo credit: © Ezgi Kilincaslan 2025.