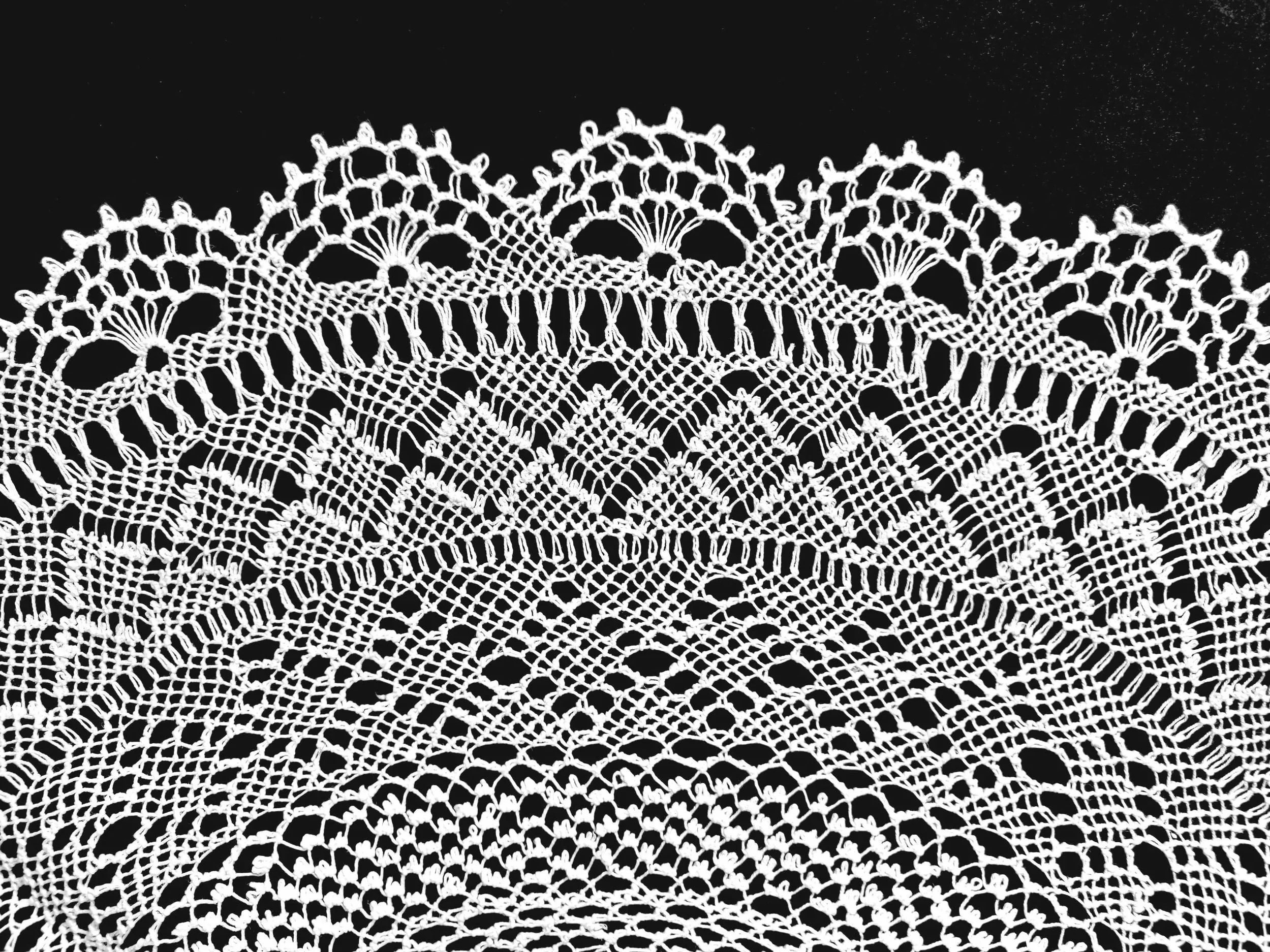

Armenian needlelace doily with pattern known by several names, including կամուրջ (gamourch), meaning “bridge”—the open pattern shown above. From the collection of Arousiag Bedrosian (b. Kadıköy, Istanbul, 1936; d. Los Angeles, California, 2024), given to her goddaughter Elise Youssoufian by Arousiag’s daughters after her passing. Photo credit: © Elise Youssoufian 2025.

on needlelace

We inherited a manual to heal these wounds!

Armenian women are taught from a very young age how to sew and craft needlework. My mother tells me it was to distract them from the sounds of war and violence. Others sold it to survive.

Kamee Abrahamian

“Herstories of Divine Love,” 2018 [1]

introduction

As artists and scholars, we at the Armenian Needlelace Initiative—a collaboration between co-founders Deborah Valoma and Elise Youssoufian—present a short overview of the complex history of Armenian needlelace, offering cultural contexts and personal reflections on our ancestral tradition.

As strong as it is delicate, Armenian needlelace, an ancient and living form of intricate needlework, evokes fields and mountains of home and connects ancestral lines dispersed throughout Armenian lands and diasporas worldwide.

Typically stitched with cotton thread, every intersection in the overall structure is formed by a single knotted loop; if one part is damaged, the body remains intact. Armenian needlelace’s paradoxical qualities of fragility and strength pervade the spirit of the tradition and its makers during everyday pleasures and extraordinary hardships.

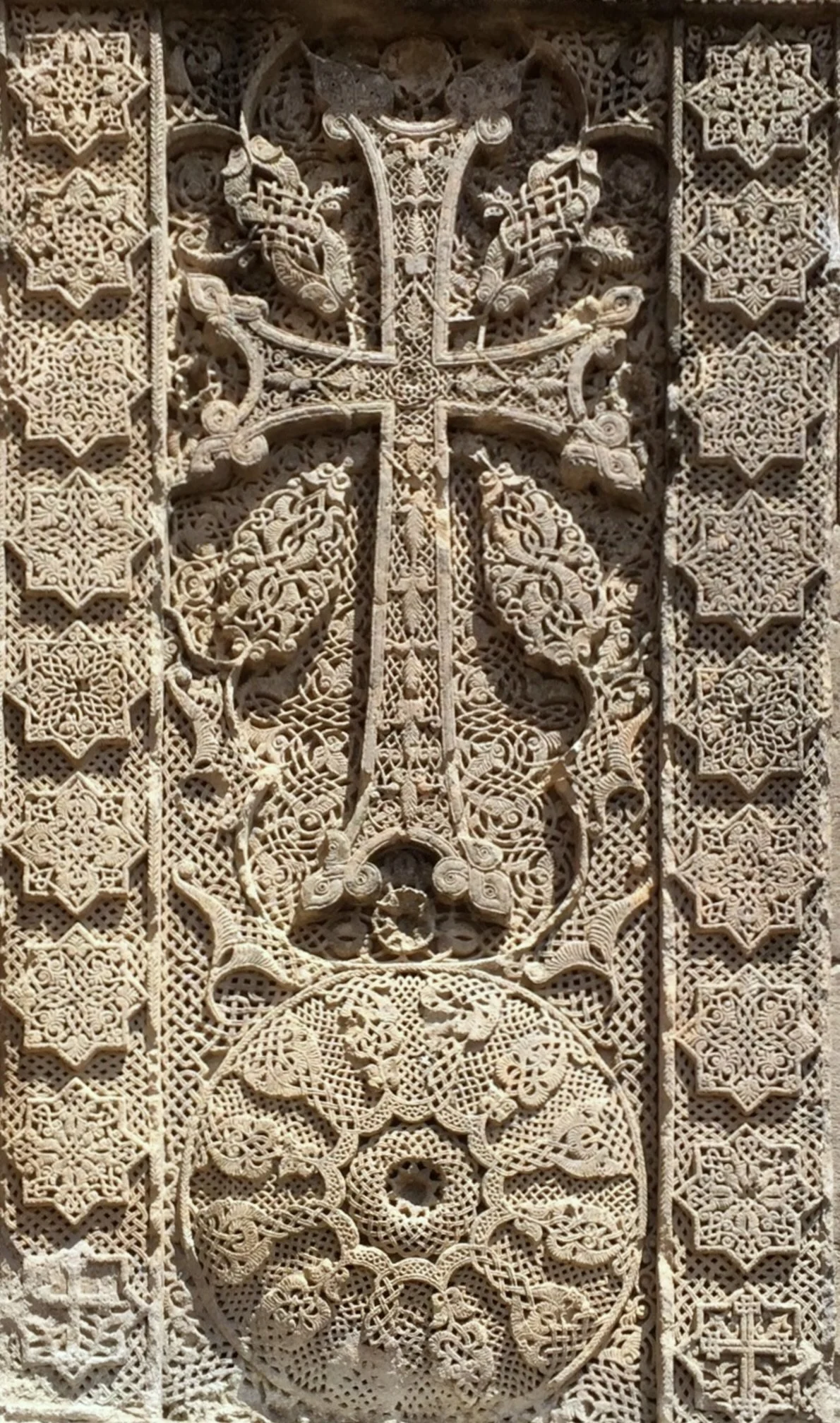

The lace's distinctive interlacing patterns are thought to invite health and prosperity and trap or confuse evil spirits and intentions. [2] Depicting Earth-honoring elements of culture and place, such patterns also appear on ancient Armenian architecture, silver work, and stone carvings (see image 1) to protect and adorn the sacred. [3]

Image 1. Master Poghos, Khachkar (cross-stone), known as Aseghnagorts (Needlework), Goshavank Monastery, Tavush Province, Armenia, 1291. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Armenian folk arts expert Anush Sharambeyan notes that “the patterns created in fine needlework [typically gendered female] are natural shapes for thread to take and considerably less natural for silver or stone [work, typically gendered male].” In citing one contemporary needlelace artist’s theory that men “would inevitably reflect the aesthetics” of women’s crafts embedded in their childhoods, Sharambeyan suggests that thread may have been “the original medium” for the patterns. [4] We concur with this assessment; visual designs naturally emerge from the interlacing of thread and have migrated to smooth surfaces such as ancient painted Incan ceramics, Muslim tile architecture, and Celtic stone carving. [5]

domestic art

Needlework in general, and needlelace in particular, was historically practiced as a domestic genre by Armenian women living within the patriarchal society of the Ottoman Empire. As Sharambeyan asserts, embroidery and needlelace were valued “as one of the few forms of expression open to women” in the domestic sphere. Skills in threadwork signaled the feminine virtues of domestic industriousness and wifely silence, but also gave women a creative “voice.” [6]

Of the many textile techniques practiced by Armenian women (e.g., embroidering, knitting, crocheting, spinning, cloth and carpet weaving, etc.), needlelace held an elite status. [7] Because of its technical complexity and meticulous designs, the technique takes many years to perfect. Historically, girls began learning at a young age, often as early as six or seven; the copious hours needed to become proficient often conflicted with a girl’s formal education beyond elementary school, which in some cases was either discouraged or unavailable.

Needlelace pieces were made for an Armenian woman’s dowry, decorated the home in the form of doilies and table runners, and trimmed personal items such as handkerchiefs, headscarves, and collars. Lacemaking provided women with the means to create and circulate female wealth in the form of trousseaux and gift exchanges. Makers also donated their work to churches in acts of religious devotion to cover altars and for priests to carry crosses during ceremonies. Furthermore, the commodification of needle skill also empowered women with a means to generate a livelihood in perilous economic times.

According to many scholars including Yaşar Tolga Cora, professor of history at the Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, amid and in the wake of the Armenian Genocide (1915–1923) and waves of prior massacres (e.g., Hamidian, 1894–1896; Adana, 1909), needlework became a critical strategy of survival. Through the efforts of teachers, missionaries, and merchants who organized workshops to meet the moment in desperate times, it served to help tens of thousands of widows and orphans escape poverty, rebuild community, and preserve Armenian traditions. It was also a vehicle for (co)creating paths towards personal and collective healing. [8] Likewise, in 2020 and 2023 when more than one hundred thousand indigenous Armenians were permanently displaced from the autonomous enclave of Artsakh (a.k.a., Nagorno-Karabagh) in present-day Azerbaijan, we see the pattern of suffering and survival through handwork continuing to this day.

origins

Image 2. Bronze statue of the deity Arubani/Anahit, Urartu/Ararat, eighth to seventh centuries BCE. History Museum of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia, No. 1242. Photo credit: © Ekaterina Kriminskaia (via dreamstime.com).

In exploring the underresearched topic of Armenian needlelace, we find that our investigations often lead to more questions than answers. Because ancient textiles do not last millenia unless in consistently wet, dry, or frozen environments, the date and location of knotted needlelace’s origins are unknown. However, it is worth noting that the low-tech practice, for which only needle and thread are required, is very likely thousands of years old. As groundbreaking Armenian textiles scholar Serik Davtyan and others observe, there is evidence of feminine figures wearing lace-trimmed head coverings on ninth-to-seventh century BCE statues and coins (see image 2) found in the historic Armenian Highlands, in present-day eastern Türkiye and the Republic of Armenia. [9]

Drawing upon the work of Davtyan and other scholars, expert needlelace maker and author Alice Odian Kasparian proposes that, like various theories on Armenian civilization as a whole, [10] Armenian practices of needlelace may have begun in Vaspurakan, the ancient kingdom centered around Lake Van (in present-day southeastern Türkiye and northwestern Iran; see image 3). [11] Leading Armenian needlework teacher, author, and lecturer Lusine Mkhitaryan echoes Davtyan in noting an important distinction. Namely, while Armenian practices of two-dimensional lace are likely from Van, three-dimensional needlelace is thought to have originated northwest of Van in the historic province of Garin (now known as Erzurum, in eastern Türkiye). [12]

Yet unlike other forms of Armenian needlework primarily associated with specific regions (e.g., Antep, Marash, Svas, Urfa, etc.), by the nineteenth century, needlelace-making was practiced throughout much of historic Armenia. [13] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the tradition’s reach grew further still as Armenian survivors of violence from disparate locales crossed paths in orphanages and refugee camps and shared patterns worked by their foremothers’ hands.

Today, regardless of where Armenians are born we often identify ourselves by our ancestral lands and threads. Thus, though a scholarly study of regional differences remains to be written, needlelace can—much like the pattern called կամուրջ (gamourch), meaning “bridge” (see banner image)—bring us across to a sense of home. Like many thread traditions across the world, Armenian needlelace is, for us, a practice of healing.

cultural connections

At the Armenian Needlelace Initiative, we are dedicated to knotted needlelace traditions as practiced past and present by Armenians in relationship with ancestral lifeways and lands. We are likewise intrigued by the cultural tie-ins between regional needlelace practices that show connections between women from several Southwest Asian and Eastern Mediterranean cultures—e.g., Armenian, Greek, Turkish, and Palestinian (specifically Nazarene). These traditions are known by different names in different languages; they are noted here to underscore cross-cultural connections.

Western Armenian: ձեռագործ (tserakordz) or ասեղնագործ (aseghnakordz)

Eastern Armenian: ասեղնագործ ժանյակ (aseghnagorts janyak)

Greek: μπιμπίλα (bibíla) or πιπίλα (pipíla)

Turkish: iğne oyası (ine oyasi)

Arabic: التيب (teib)

With overlaps and distinctions between the often fluid symbolic meanings of individual patterns and overall composition, these diverse and yet related traditions are kept alive by a small-yet-notable body of makers and teachers worldwide. These culture bearers are dedicated to maintaining the tradition and to ensuring its longevity.

Cross-culturally, knotted needlelace can be two-dimensional (e.g., doilies, tablecloths, trims, etc.) or three-dimensional (e.g., for brooches, headpieces, trims, etc.). For example, our research suggests that it is common for modern Turkish and Kurdish needlelace makers in Türkiye to create multihued two- or three-dimensional works, and for Armenian makers in Armenia, Türkiye, and the diaspora to create two-dimensional laceworks in shades of white, and perhaps less commonly, polychromatic three-dimensional works. Additionally, in our observations, most antique Armenian needlelace collections—including our own—seem to consist mainly of white or off-white two-dimensional lace. Therefore, we find ourselves especially drawn to and especially focused on such works, which call to us from our own foremothers.

It is important to note that “knotted” needlelace is different from the wide range of more recently developed European techniques, commonly called needlelace, which date from the Renaissance onward. However, European influence can be seen with the introduction of brightly-colored threads achieved with aniline dyes in the mid-nineteen century and variegated threads in the mid-twentieth century, both of which provided lace makers means to explore new and uncharted aesthetic paths.

precarious present

Traditionally, children learned Armenian needlelace and other forms of ancestral handwork from their female relatives, neighbors, and friends in a continuous line of succession. But this form of transmission has become increasingly discontinuous. In addition to the economic, social, and familial fractures experienced by Armenian populations during the massacres and genocide, needlelace skills—like many other textile traditions worldwide—have been impacted by the conditions of modernity. Multiple factors have taken their toll: the affordability of mass-produced substitutes; universal education of girls; increased employment and career opportunities for women; and in the Armenian diaspora, a declining identification with one’s heritage under the pressures of assimilationism.

It is salient to note that three conditions perpetuate the continuation of hand-crafted textiles within contemporary industrialized production schemes: 1) the opportunity to produce capital in economically depressed areas or during periods of limited economic opportunity (e.g., rug weaving on the isolated Diné (a.k.a., Navajo) reservation and Irish lace making during the 1846 Famine); 2) the evolution of textiles from utilitarian or decorative objects into expressions of cultural identity (e.g., Palestinian tatreez [cross-stitch] and Native American basketry); and 3) the production of textiles as repositories of memory and mourning (e.g., South African mapulas [embroidered narratives] and the American AIDS Memorial Quilt).

The evolution of Armenian needlelace seems to track along these trajectories. For some, it remains a source of income. For others, the act of making has become a strategy of resistance—a means to reclaim and proclaim ethnic identity in the wake of ethnic violence, to hold fast to cultural through-lines, and to create a sense of home within the refugee experience of dislocation. For others still, stitching needlelace functions as an unspoken, and perhaps unacknowledged, work of silent mourning when speaking loss was unthinkable. And in some cases, practitioners are moved by all three motivations.

fledgling movement

Even preceding our initial meeting in 2022, each of us had perceived a curious and inspiring convergence of events. At the same moment across the globe, a seedling of interest in Armenian needlework—including needlelace—seemed to be growing among young Armenians. Furthermore, new teachers have emerged offering novel learning opportunities such as virtual classrooms and instructional videos, in addition to recent publications. As early as 2019, Deborah and Elise began meeting independently with elder practitioners, as well as young people who were interested in learning about needlelace, each in their own way. Based on our individual and joint research in the United States, Türkiye, Armenia, and beyond, this fledgling movement is gaining momentum, evidenced by recent articles such as “Threading Traditions: Meet the Artists Weaving New Life into Armenian Embroidery.” Today, doors are opening to allow makers to expand aesthetic conventions, transform uses and display practices, and cross gendered boundaries.

In this context, we contend that picking up needle and thread is a strategy for ensuring cultural survival, encouraging personal and collective healing, building group solidarity, and (re)creating repositories of memory. We therefore propose a recontextualization of the genre as it diverges in meaning from a domestic expression (signature of gender) to a statement of resistance and survival in the post-genocide experience (signature of ethnicity). We celebrate and participate in these evolutions, as we recognize that the continuation of the genre requires both preservation and innovation.

This website is designed to support and participate in this growing movement.

Deborah Valoma & Elise Youssoufian

Co-founders, Armenian Needlelace Initiative

January 1, 2026

Image 3. Historic Armenian kingdoms (present-day eastern Türkiye and the Republic of Armenia, as well as parts of northwestern Syria and Iran, western Azerbaijan, and southern Georgia). Map from Britannica’s “History of Armenia” entry (via Britannica.com).

[1] Kamee Abrahamian, “Herstories of Divine Love,” The Armenian Review: Queering Armenian Studies 58, nos. 1–2 (2018): 178.

[2] Alice Odian Kasparian, Armenian Needlelace and Embroidery: A Preservation of Some of History's Oldest and Finest Needlework (McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1983), 22-24; Armenian Textiles Exhibit, Armenian History Museum (Yerevan, Armenia, 2019); Hamlet Petrosyan, “The Khachkar or Cross-Stone,” in Armenian Folk Arts, Culture, and Identity, eds. Levon Abrahamian and Nancy Sweezy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 63-64; Lusine Mkhitaryan, Հայկական Ասեցնագործ Ժանյակ: Վարպետության Դասեր (Armenian Needle Lace: Master Classes) (Yerevan: Zangak, 2018), 7.

[3] Hamlet Petrosyan, Khachkar (Yerevan: Zangak: 2015), 33-34, 42-43.

[4] Anush Sharambeyan, “Needle Arts,” in Armenian Folk Arts, Culture, and Identity, eds. Levon Abrahamian and Nancy Sweezy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 171.

[5] Deborah Valoma, “The Permanent Made Permanent: Textiles, Pattern, and Migration of a Medium,” Fiberarts 32, no. 3 (2005): 44–49.

[6] Sharambeyan, “Needle Arts,” 165.

[7] Sharambeyan, “Needle Arts,” 169.

[8] Yaşar Tolga Cora, “Making Crafts for Survival: Armenian Women and Textile Production after Violence (1894-1920s),” Centre for Western Armenian Studies, October 23, 2025, webinar.

[9] Serik Davtyan, Հայկանկան Ժանյակ (Armenian Lace) (Yerevan: Armenian USSR Academy of Sciences, 1966), 51; Kasparian, Armenian Needlelace and Embroidery, 25–36.

[10] Matthew Karanian, Historic Armenia After 100 Years: Ani, Kars, and the Six Provinces of Western Armenia (Northridge, CA: Stone Garden Press, 2015), 76–84.

[11] Kasparian, Armenian Needlelace and Embroidery, 25–36.

[12] Mkhitaryan, Հայկական Ասեցնագործ Ժանյակ (Armenian Needle Lace), 7–8, 55.

[13] Mkhitaryan, Հայկական Ասեցնագործ Ժանյակ (Armenian Needle Lace), 8.

• back to the top •