crossing the bosporus

deborah valoma

And in this dream, our hands

Rest on mossy stones, cooling

Palms burning with beings

Who see ash and still taste sky,

Whose stories know where to flow

Elise Youssoufian

“Darkness, Dancing,” 2022 [1]

Dzaghig (hands folded) with members of Zeynep Taşkın’s family, Ankara, Türkiye, ca. 1930. Left to right: Sıdıka Kınacıt (grandmother), Dzaghig, Naciye Kınacı (mother’s sister), and Kamile Kınacı (mother’s sister). Photo: © Zeynep Taşkın.

It was raining that day in November 2023 when Zeynep Taşkın generously accompanied me across the Bosporus from Karaköy to Kadıköy to meet a friend. As we sailed eastward to the Asiatic side of Istanbul, we sat inside the ferry in soaked clothes. Zeynep sat on my right next to the window; the sky was dark and the view of the cityscape through the windows was blurred with fast-flowing rivulets. She carefully pulled out two pieces of age-worn needlelace from her bag and held them in her outstretched hands.

In a quiet voice she told me the story of an Armenian woman, Dzaghig, who had lived in her grandfather’s house. According to family history, Dzaghig’s husband died in the Armenian Genocide (1915–1923), and was saved from a similar fate by Zeynep’s Turkish family. Dzaghig lived in their home first in Ankara, and after they moved in the 1930s, in Istanbul until her death in 1942 . She is buried at Yerevman Surp Haç Ermeni Kilisesi Mezarlığı, located in the neighborhood of Kuruçeşme. Sadly, her last name is currently unknown.

To the casual onlooker on the ferry, the moment appeared mundane. But for us, it cracked open a painful history. She was unsure of the details of the story, Zeynep said. She looked at me closely, hoping I would understand the historic complexities without words. And I did. During the genocide, Armenian girls and women were taken to live in Muslim households under varying degrees of violence, coercion, and kindness. Some accounts—and I heard this directly from an Armenian family in Jerusalem—describe mothers smearing their daughters’ faces with mud to disguise and hopefully prevent them from being raped or abducted and subjected to sexual servitude. Other accounts describe Armenian mothers relinquishing their children to Turkish, Arab, and Kurdish families in a desperate effort to shield them from starvation, disease, and the murderous actions of the Turkish gendarmes. [2] Yet other less-common narratives recount acts of compassion in which Armenians were hidden, adopted, or married into Muslim households. [3]

At the end of World War II, some Armenians escaped from Muslim households or were rescued by humanitarian and missionary organizations committed to reintegrating them into Armenian society. But because these efforts were, in addition to philanthropic, also a strategy of Armenian “national reconstruction,” some young mothers had to make the painful choice to leave behind children. Considered by some to be only the offspring of the perpetrators, they were not always accepted into shelters and orphanages. [4] Other women chose to stay with their children in Muslim households and assimilate, often concealing their ethnic origins from their descendants and sometimes forgetting their native culture, given names, and mother tongue.

Located only an hour’s drive away from Deborah’s ancestral villages around Elâzığ, Türkiye, Zeynep and Deborah traveled together to the reconstructed Armenian fountains at Habap (Ekinözü) in November 2025, which marked the 130th anniversary of the beginning of Hamidian Massacres in that area. Video credit: © Deborah Valoma 2025.

These hidden stories have become more widely known in the last two decades after the publication of Turkish lawyer, writer, and human rights activist Fethiye Çetin’s 2004 narrative My Grandmother: An Armenian-Turkish Memoir. In it, the author describes her grandmother’s deathbed revelation of her hidden Armenian heritage. Fethiye and Zeynep have known each other well for many years and fifteen years ago worked together on a project to rebuild two Armenian fountains in the village of Habap (present-day Ekinözü), where Fethiye’s Armenian grandmother had grown up. The project is described in the documentary Habap Fountains: The Story of a Restoration.

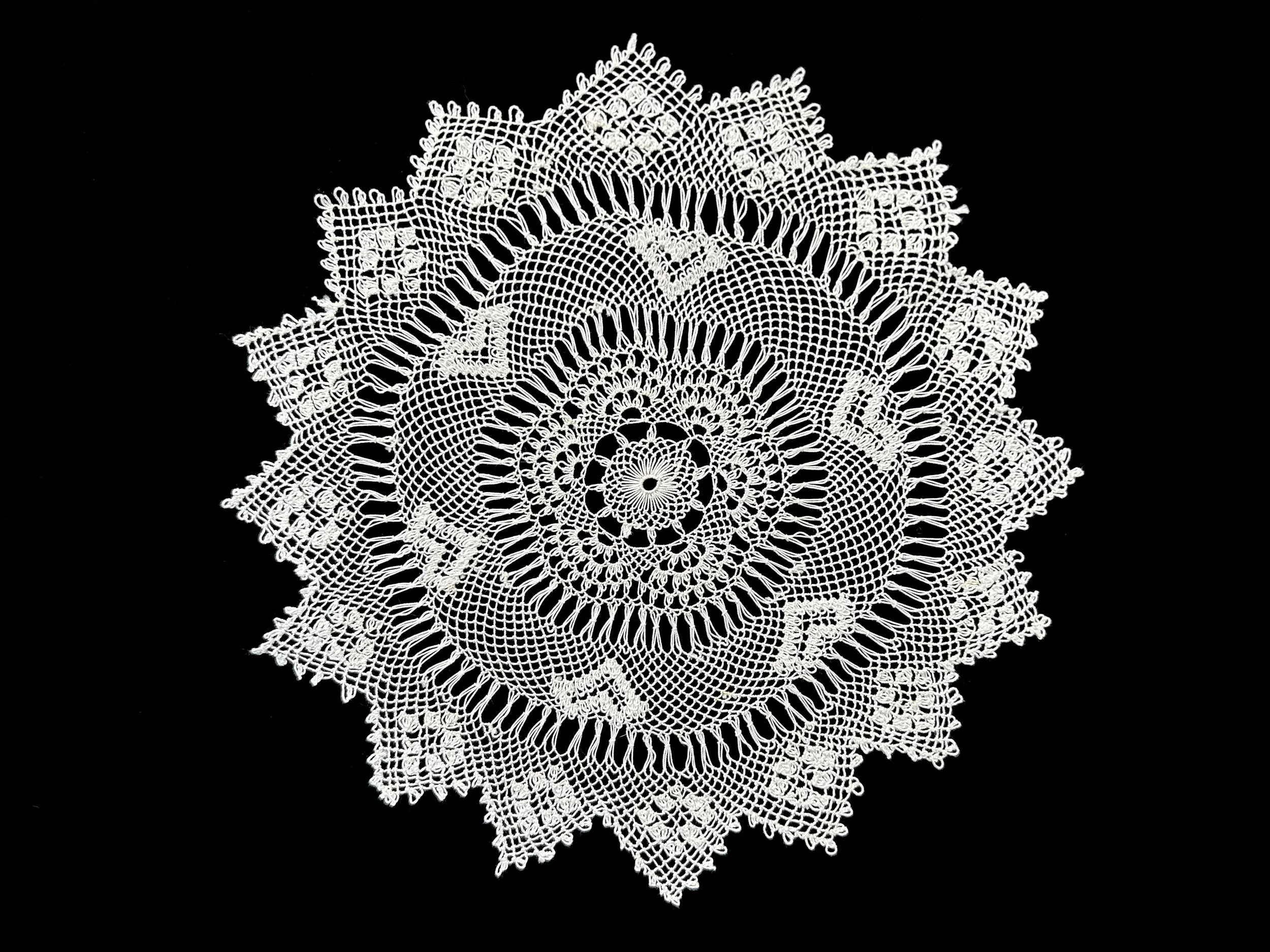

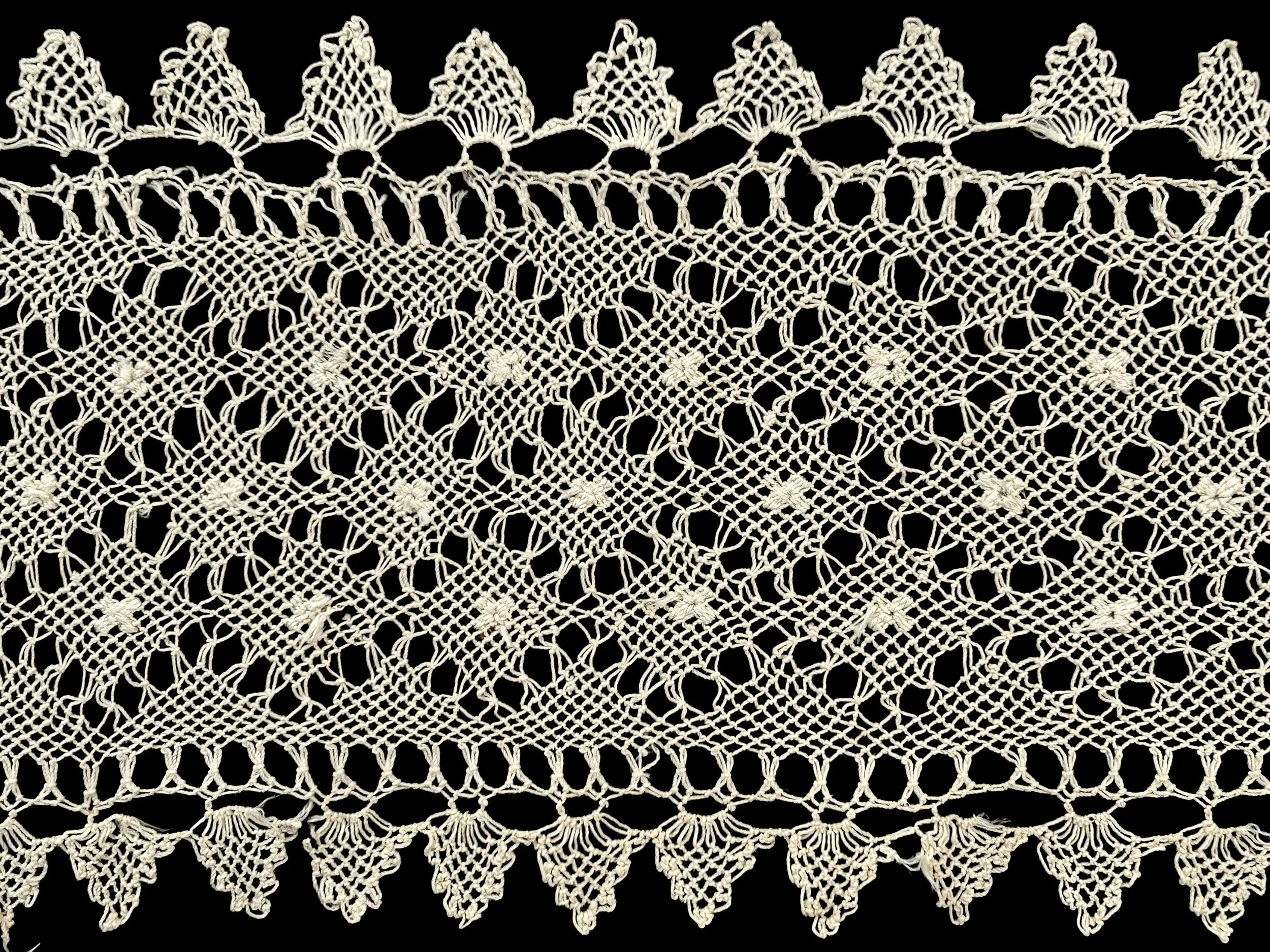

Zeynep and I quietly sat together as these histories, coated with sorrow, flowed around and between us. She tenderly handed me the needlelace pieces—the first a worn rectangular collar stitched in cream-colored cotton and the second a white circular doily. I was surprised when she softly said: “Please take them. You’ll care for them.” Both of us felt the sharp poignancy of the moment—a quiet, almost imperceptible moment of making things right, a rematriation of fragile threads.

Little did the lacemaker Dzaghig know that one hundred years later, a Turkish woman would gift these treasures—one of the few remnants of her existence—to an American woman of Armenian descent. She could not have known that her work would be transported to the United States—perhaps a place that Dzaghig had imagined a refuge—to be carefully washed, photographed, wrapped safely in archival tissue, and put to rest.

Heirlooms keep falling into my hands.

[1] Elise Youssoufian, “Darkness, Dancing,” in Spoon Knife 10: Polarities (Fort Worth, TX: Autonomous Press, forthcoming in May 2026).

[2] Elyse Semerdjian. Remnants: Embodied Archives of the Armenian Genocide. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2023).

[3] George N. Shirinian, “Turks Who Saved Armenians,” Genocide Studies International 9, no. 2 (2015): 208–227.

[4] Vahé Tachjian, “Gender, Nationalism, Exclusion: The Reintegration Process of Female Survivors of the Armenian Genocide,” Nations and Nationalism 15, no. 1 (2009): 60–80.

Dzaghig (last name unknown), needlelace doily, ca. early twentieth century, Ankara or Istanbul, Türkiye. Gifted to Deborah Valoma by Zeynep Taşkın. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2023.

Dzaghig (last name unknown), needlelace collar, ca. early twentieth century, Ankara or Istanbul, Türkiye. Gifted to Deborah Valoma by Zeynep Taşkın. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2023.

Dzaghig (last name unknown), needlelace collar (detail), ca. early twentieth century, Ankara or Istanbul, Türkiye. Gifted to Deborah Valoma by Zeynep Taşkın. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2023.

Dzaghig (last name unknown), needlelace doily and collar, ca. early twentieth century, Ankara or Istanbul, Türkiye. Gifted to Deborah Valoma by Zeynep Taşkın. Photo credit: © Deborah Valoma 2023.